AGRYOS: Recovering Eden

Producer

June 2021 - December 2021

AGRYOS: Recovering Eden was created by 16 developers over a span of 5 months at SMU Guildhall as part of their Capstone curriculum.

At SMU Guildhall, the curriculum includes three Team Game Project courses, where students learn about interdisciplinary collaboration by creating a game from concept to release. The first is a mobile game, which you can read about here, and the second is an arcade racing game for PC, detailed here. During Capstone, the team spends five months over the course of two semesters developing a portfolio piece that demonstrates their ability to create professional-level work—this postmortem will document that experience.

My contributions:

Led planning sessions with team leads & executive management, highlighting priorities, departmental interdependencies, resource issues, and risks

Tracked team progress toward biweekly milestones & mitigated risks by implementing contingencies and/or cutting features as appropriate, reducing crunch & amount of rework

Oversaw localization from inception to completion, coordinating with translators to deliver a high quality translations that connected a broader audience to the game

Table of Contents

The Idea

The idea took form in a team-wide brainstorming session and evolved over time. At first, we wanted to do a cyberpunk game in a High Gothic world, but realized that the environment would be too ornate and over-scoped for our team. Instead, we turned to Mughal architecture for inspiration. From there, the world took shape, and our sci-fi shooter found its footing on the alien planet of Axenum—an abandoned space colony with crucial resources the player fights to recover from rogue robots. We used diverse enemy types to encourage the player to use a variety of weapons in intense, arena-style combat, keeping our defining mantra (“zoom & boom”) in mind to ensure every feature in the game created a zippy, explosive experience for the player.

Developing the Robots

A roundtable between the leads highlighting how our process came together throughout the project.

The Process

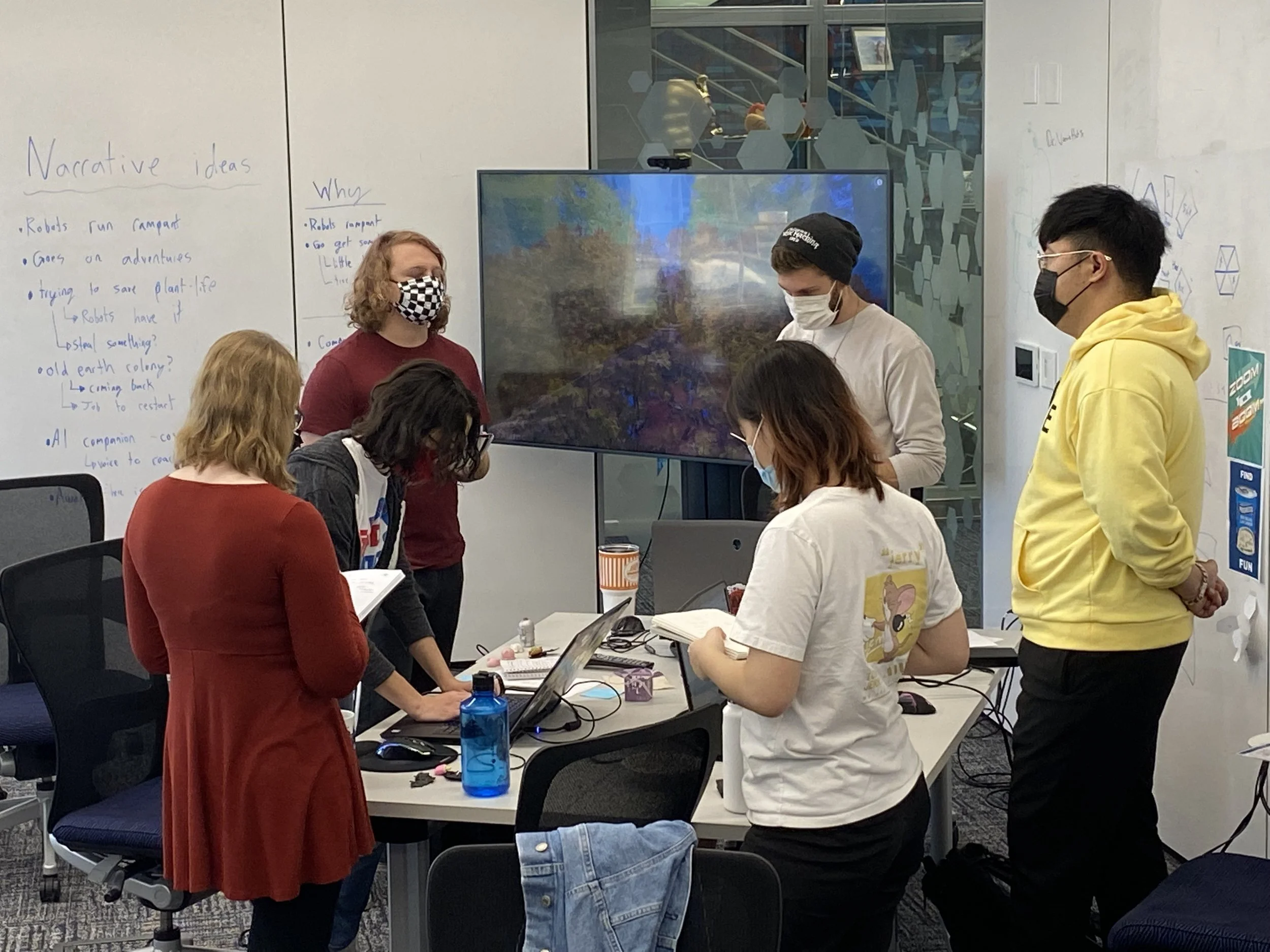

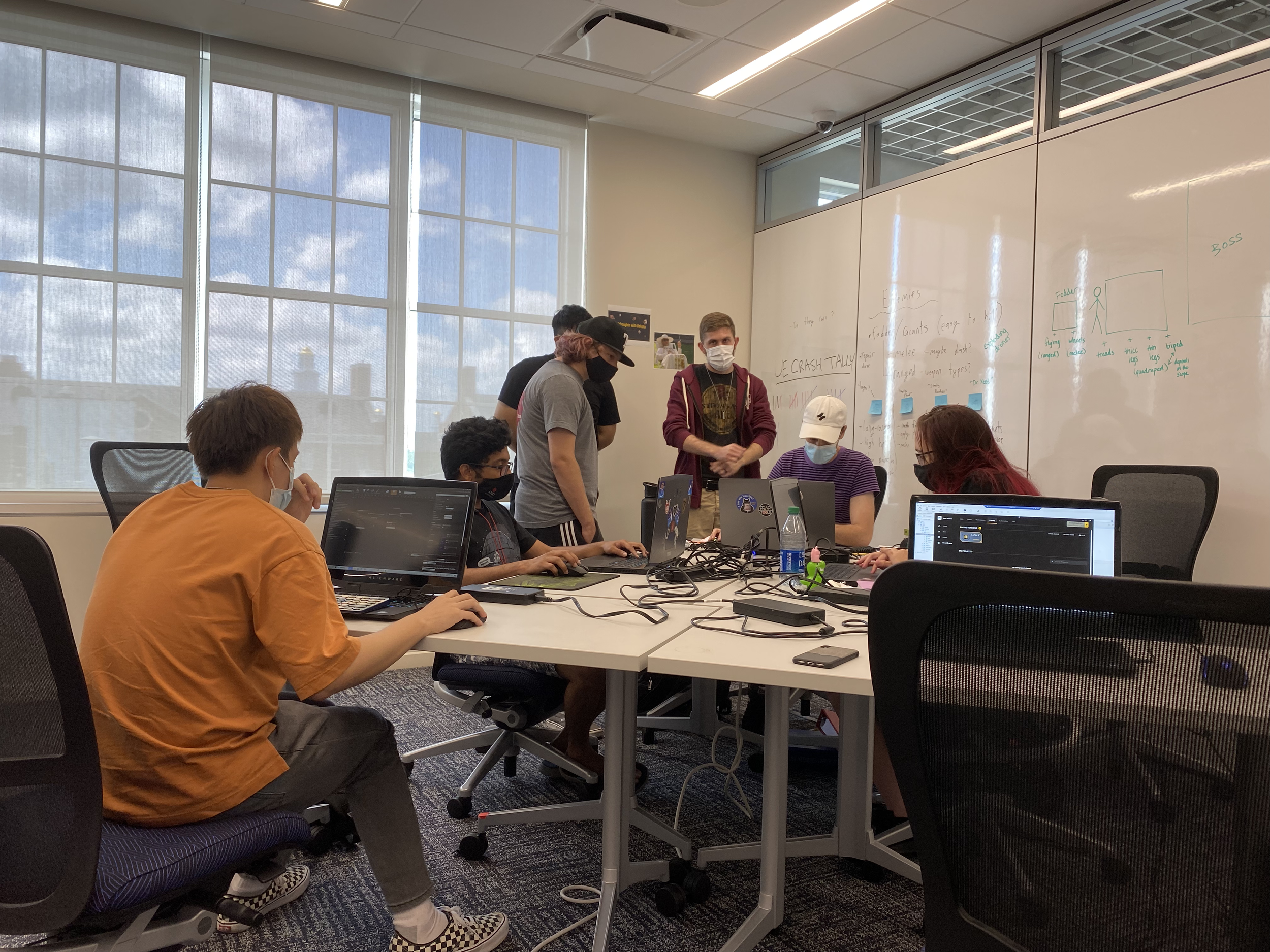

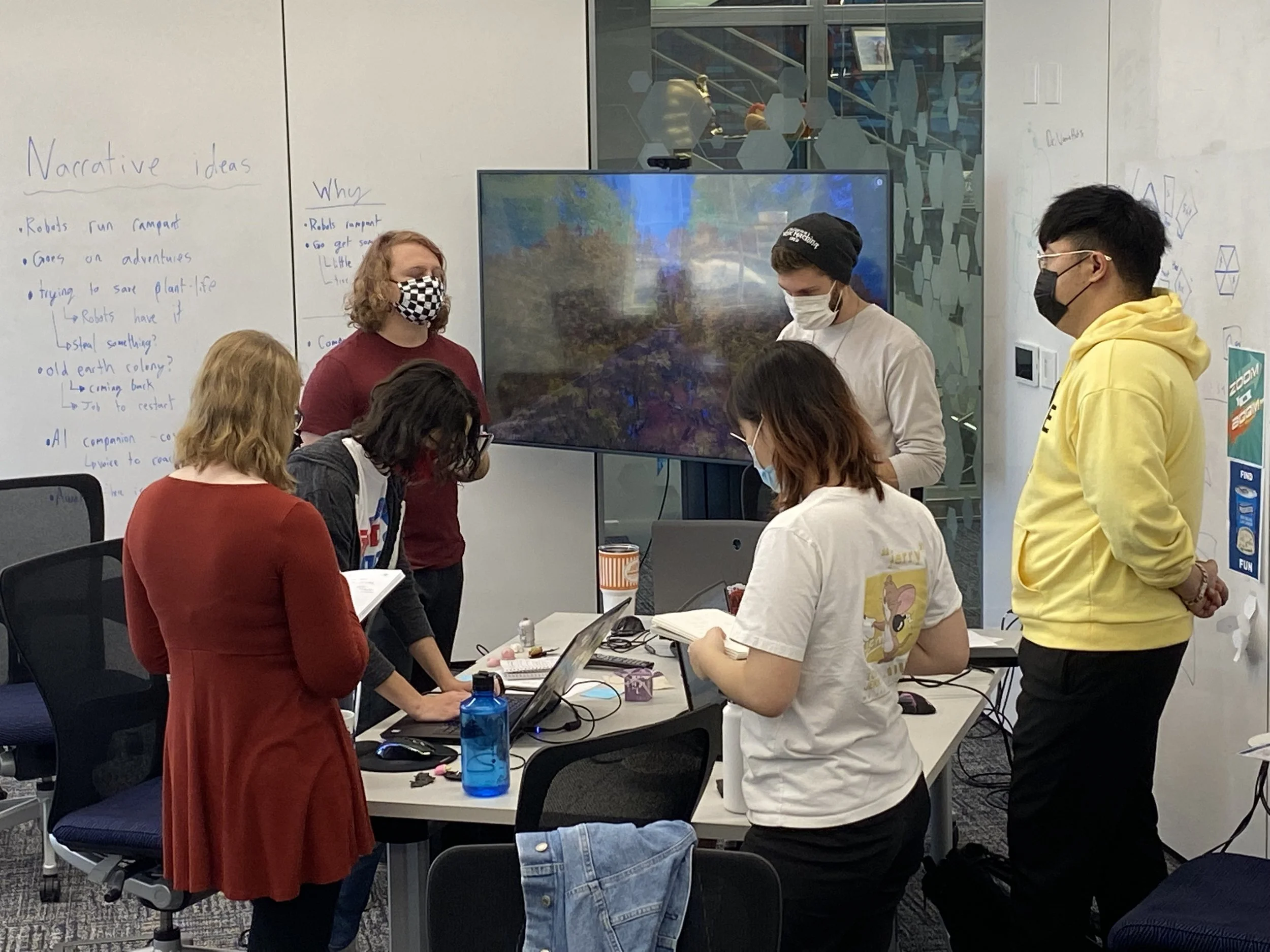

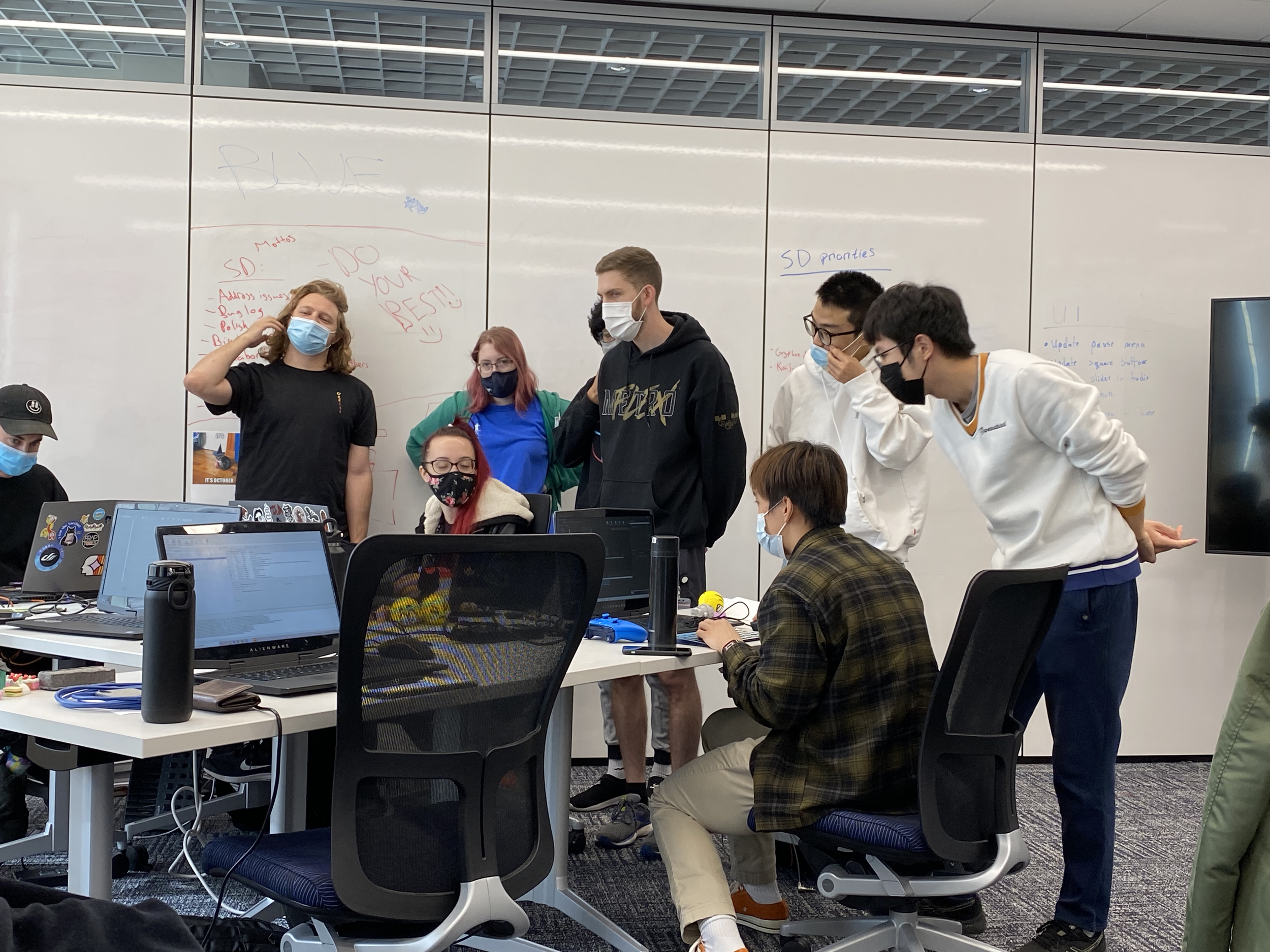

Nearly every day before work began, the leads would meet to discuss the game’s progress and set the day’s priorities. These meetings usually began with a playtest of the latest build and a thorough critique of what we had onscreen—this way, we were able to rapidly address bugs or reassess a task’s importance so that we could make the most of our short timeframe. Like on Snowpainters, our work days were three hours long with two-week milestones, so efficiency was key.

Because AGRYOS: Recovering Eden was developed during the pandemic, work was primarily done in person but set up to accommodate remote teammates. During our preproduction phase, two of our artists were still in China, working asynchronously and checking in daily until they arrived in Texas. Throughout development, we used Owl cameras, a main Zoom room, and breakout rooms for hybrid collaboration to great success, keeping the team strong even when physically apart.

The Leads Team

What Went Well

Reliance on Experts

In addition to our own research to evoke the grandeur of Islamic architecture in our setting, we relied on the expertise of our sensitivity reader, Dr. John Lamoreaux. His advice ensured we were able to translate that inspiration into a world unique enough to stand on its own. Additionally, his direction for our protagonist character, Neziha, was invaluable as we refined our design. We met with him several times throughout development, sharing concepts and in-progress work for his feedback, until our leads team felt confident that our players would enjoy exploring Axenum as much as we did creating it.

As the game took form, we did user testing two to three times per milestone with a diverse group of playtesters, getting good feedback on the world we created and what sort of impressions it made on the player. Once we implemented our character model in-engine, we began specifically seeking out Muslim playtesters, particularly women, to verify if we’d been successful in following Dr. Lamoreaux’s advice. Being able to rely on the feedback of people whose expertise came from their cultural background, lived experience, and academic research gave us the confidence to design a unique protagonist and setting that we were proud to stand behind.

Developing Neziha

A discussion with our Lead Game Developer & Lead Artist detailing how Neziha’s character evolved over time.

Communication with Stakeholders

Throughout development, we frequently communicated decisions to our stakeholders outside of milestone presentations. The riskier the decision, the sooner we informed them. For example, we initially committed to an isometric perspective in preproduction, then realized right before production began that a third-person camera would be more appropriate. Another example was when we decided to create a veiled female protagonist to explore our Islamic-inspired, sci-fi setting. By communicating these ideas early on and discussing the anticipated risks, we not only built trust with our stakeholders, but also gave them the opportunity to provide us with resources and advice to make implementing those decisions easier on the team.

High Performing Team

One of our greatest strengths as a team was having so many skilled individual contributors. During preproduction, we created many different mechanics to play around with our game’s combat feeling, including grenades, placeable turrets, and a Captain America-style bouncing shield. Additionally, our art team was able to rapidly iterate on environmental assets and robot designs as we refined our aesthetic. By quickly implementing these features, we were able to explore our game’s identity very broadly before paring down to the core of AGRYOS. While only a fraction of that investigatory work made it into the final product, its development made it possible for us to find the soul of our game.

Prioritizing Gameplay

Building off the previous point, once we had our core pillar of “zoom & boom,” we were able to reassess our game’s features to see how well they fit into the game’s identity. Any work that muddied our intended experience (like snapping to cover or stealth) was cut, and we focused on polishing what remained.

We also spent a lot of time early on developing a much more ambitious narrative than what we shipped. As we continued refining our levels’ layouts, we realized that making space for those narrative moments would take away from polishing our combat. Instead, we used optional pickups to share lore with the player, following our core pillars to create an uninterrupted gameplay experience. AGRYOS was stronger for it, as is reflected in how well-received our game was on Steam.

Prioritizing QA

Finally, we prioritized QA from the very beginning. During preproduction, we pulled an all-stop halfway through every work day and had everyone on the team play the game for 30 minutes. Once we moved into development, we organized at least two user testing sessions with new players every milestone, going through the feedback with a fine-toothed comb before deciding how to act on it. Our Lead Game Designer Dakota Loupe, my co-producer Richard Bai, and I spent a good amount of time every milestone refining our playtest surveys to ensure that feedback was relevant and answered the right questions.

Additionally, we started every leads meeting with a thorough bug hunt. Dakota would play through a different section every day, highlighting how the previous day’s work was showing up in the latest build. This way, every day was focused on addressing the highest priority issues, staying on track to meet our milestone delivery goals, and creating the best shooter game we could.

What Went Wrong

Long Iteration Cycle for Protagonist

Because our protagonist's design was so important to us, we spent four milestones (nearly half our development time) exploring different options until we found the right one. Some of our artists preferred sculpting to drawing thumbnails and spent the first few weeks 3D modeling, slowing down iteration time until we went back to basics. Our first few character designs were affectionately nicknamed “Doom Girl,” since she looked like a female Doom Slayer. It wasn’t quite what we wanted, though, and our sensitivity reader had some concerns, so our Lead Artist Lauren Dube came up with some different ideas with his feedback.

After seeing the new concepts, though, some of the team felt that the design came off less like a protagonist and more like an NPC, or that her design didn’t seem to match the character’s aggressive movement style. To address this, the leads spent a lot of time talking to the team to understand their perspective and explain our decisions, which eventually helped them see our direction more clearly. Because all of us were so unfamiliar with the background we gave our protagonist, and because of how loosely defined our concepting process was, it took much longer than expected to develop the final design. Had we asked Dr. Lamoreaux for some guidelines before concepting, and had a more traditional concept pipeline, we could have saved ourselves a bit of time earlier on and approved a concept sooner.

Role Confusion

With only 16 people on our team, each with a variety of skills and experiences, many of us took turns wearing different hats in order to execute our ambitious vision. Dakota designed his own level in addition to directing the game. Richard developed much of the game’s HUD and UI before we assigned artists to it. While these eventually led to a strong shipped product, these blurred roles created confusion for the team and muddied our production pipeline as development progressed.

The biggest issue was my role as Narrative Lead. We had a formidable narrative, but no narrative designers, so between my production tasks, I worked with Dakota to execute his vision. When the leads would review the level designers’ work, I was invited to give my feedback as well—however, I never took the time to explicitly state, “This is my feedback as Narrative Lead, not as a producer.” Since I didn’t clarify which hat I was wearing and when, my input came across as overstepping. This also had the unintended effect of making it harder to vision-keep for the other leads, since the team was never really sure when I was working as a producer. For me to have fulfilled this dual role, I needed stronger signaling to the team for which part I was playing so they knew that I respected my place(s) in the pipeline.

Over-scoped Game Concept

While having a high performing team was a boon to us, it also gave us an unearned sense of confidence. Our initial game pitch was much more ambitious—ten unique gun assets the player could swap between; a skill tree; a large, overarching narrative—than was realistic for a five month development cycle. As we continued to reduce our scope (from ten guns to six, then to a single gun arm with three modes), the team became demoralized by their work being cut.

Before we started on a feature, we did our best to communicate to the team that the work they were doing was exploratory and that there would be an internal deadline to determine its feasibility before moving forward. And, every time we made the decision to cut a feature, one or more of the leads would sit down with the affected team members to discuss it privately before making an announcement to the team. This helped the team emotionally prepare themselves, but had its limits. We had anticipated needing to re-scope the project and took steps to help our team through the changes in direction, but had failed to anticipate how much it would impact them to see so much work lost. If we had focused on delivering a Minimum Viable Product first, it would have preserved our team’s morale and prevented crunch later on, which I’ll discuss below.

Crunch

Eventually, we came to a point where we could no longer cut features to finish the game. The work remaining needed more time than we had to reach shippable quality. During Alpha and Beta, there were two or three times when we asked the team to volunteer to work over the weekend, telling them frankly that without it, we would not be able to ship the game. We kept these times structured—scheduling the day in advance and defining the work session’s goals—and brought food for the team to thank them for going above and beyond. Structuring our overtime this way, paired with strong messaging to the team that we didn’t expect them to crunch outside of scheduled times, helped with managing morale and our remaining task estimates. More than anything, though, this experience taught us the importance of scoping realistically.

Missed Deadlines due to Breakdown in Process

Our approval process was difficult to get right. Some features had unusually long iteration cycles, leading to less frequent reviews early on and resulting in feedback that asked for bigger changes. After a few missed deadlines, we instituted additional checks outside of formal reviews to make sure everything met its conditions of satisfaction.

Sometimes, even after these additional rounds of feedback, some features still weren’t acceptable. When that happened, the leads would assess the item’s priority and decide to either cut or reassign it. Then, the leads would sit down with the responsible individual contributor to explain their decision and give them time to understand it. We found that, in a way, it was more demoralizing to have a task reassigned than cut altogether, so it was especially important to have that conversation. While we wanted everyone to see their work through from beginning to end, our priority (especially as we missed more deadlines) was to publish a complete, polished game to Steam, and that was the messaging we emphasized to the team.

Communicating and checking in as much as possible was the best solution we found to make up for missed deadlines. While cutting helped to reduce the team’s workload, and crunching helped to create more time to complete the project, checking in early and often made sure that the other two solutions wouldn’t go to waste. Had we checked in earlier and more often in the first few milestones, we might have been able to rescope the game soon enough to have prevented needing as much crunch as we did.

Learnings

Work with Experts

When developing features the team is unfamiliar with, leads and producers can reach out to experts who can provide necessary guidance. Stakeholders can be a great resource for this—they may already have relationships in place to find the right person for the team to refer to. Using our stakeholders’ connection with Dr. Lamoreaux, our Lead Game Designer and Art Lead were able to develop an interesting design for our protagonist.

Similar options were available to any Guildhall developer to help them design their architectural spaces. On Rhome, a previous capstone project at SMU Guildhall, the game’s stakeholders had been able to connect the developers to architects who were able to consult on the level design to create a realistic house for the player to explore. Whenever possible, leads can discuss with their stakeholders what sort of experts and resources are available to them and utilize them to great effect.

Define Game’s Identity ASAP

Because our protagonist's design was so important to us, we spent four milestones (nearly half our development time) exploring different options until we found the right one. Some of our artists preferred sculpting to drawing thumbnails and spent the first few weeks 3D modeling, slowing down iteration time until we went back to basics. Our first few character designs were affectionately nicknamed “Doom Girl,” since she looked like a female Doom Slayer. It wasn’t quite what we wanted, though, and our sensitivity reader had some concerns, so our Lead Artist Lauren Dube came up with some different ideas with his feedback.

After seeing the new concepts, though, some of the team felt that the design came off less like a protagonist and more like an NPC, or that her design didn’t seem to match the character’s aggressive movement style. To address this, the leads spent a lot of time talking to the team to understand their perspective and explain our decisions, which eventually helped them see our direction more clearly. Because all of us were so unfamiliar with the background we gave our protagonist, and because of how loosely defined our concepting process was, it took much longer than expected to develop the final design. Had we asked Dr. Lamoreaux for some guidelines before concepting, and had a more traditional concept pipeline, we could have saved ourselves a bit of time earlier on and approved a concept sooner.

Communicate Different Roles’ Responsibilities

On small teams, it’s not uncommon to have developers fulfilling multiple functions. Usually those roles will be within their own discipline—our principal audio engineer, for example, also worked on our weapons system. However, our Lead Game Designer Dakota also worked as an individual contributor, developing the boss fight at the end of the game. This caused a bit of confusion in our pipeline—if our director does level designer work, then does it still need the Lead Level Designer’s approval? If our director skips to the end of the approval process, how does that impact the rest of the level design team? We managed this very delicately and with much conversation as development progressed, but had we considered our approval process before Dakota set to work, we could have prepared an answer to this question.

In cases where someone works in two different disciplines, such as my work as producer and as Narrative Lead, it can cause confusion to the rest of the team which role they’re fulfilling and when. In those cases, it’s important to clearly signal which role one is acting in, and where one’s feedback is coming from. Additionally, both of these dual roles should be official, so that the team can expect and understand this role-switching.

Make Sure the Team Understands Dependencies

When collaborating on any project, it’s important the team understands how their contributions affect the whole picture. If a level designer doesn’t complete their blockout in time, how does that impact the art team? What features can be developed in parallel? What work requires multiple disciplines’ input? By clearly explaining interdisciplinary pipelines and why locks are scheduled the way they are, the team can be empowered to collaborate more effectively.

Additionally, by explaining conditions of satisfaction for a feature clearly, individual contributors can better understand what is required of them before passing their feature onto the next developer in the pipeline. This can help prevent or reduce delays by improving iteration time. Having specific requirements can explain what it means for the project if a feature isn’t finished in time to pass down the pipeline, and reinforce dependencies’ importance.

Encourage the Team to Buy Into the Vision

Teams perform better when they feel a sense of ownership over what they’re making, and there are many ways leads can encourage this. One way is by assigning tasks that match the individual contributor’s interests—our principal audio programmer, for example, had a passion for and experience with music mixing. We utilized his skills to develop a vertical remixing system to dynamically increase or decrease our soundtrack’s intensity as needed, directing our composers to create individual stems, rather than mixed tracks, in order to achieve this.

While the Game Director’s job is to help the team buy into their vision, a producer’s job is to facilitate processes that get the team onboard. Not only do producers vision-keep for their leads, working as their partners to ensure the team understands what they’re being asked to do, they also help the team address any concerns or confusion they may have. Any feedback the team (or the producers on their behalf) pass on is the director’s responsibility to properly adjudicate, with the goal always being to get the team’s buy-in. Working together, leads and producers can communicate direction to the team, using the team’s own strengths and suggestions to make a stronger, more creative game.

AGRYOS: Recovering Eden was the final Team Game Project developed at SMU Guildhall, a capstone project we could all be proud of showcasing in our portfolios. While it was challenging, the experience was a deeply rewarding one, and we were able to create something truly impressive. I encourage you to explore our unique setting for yourself by downloading it for free on Steam today.

%20%E2%80%94%20Nooka%20Dascalu_files/Headshot_Cartoon_transparent.png)