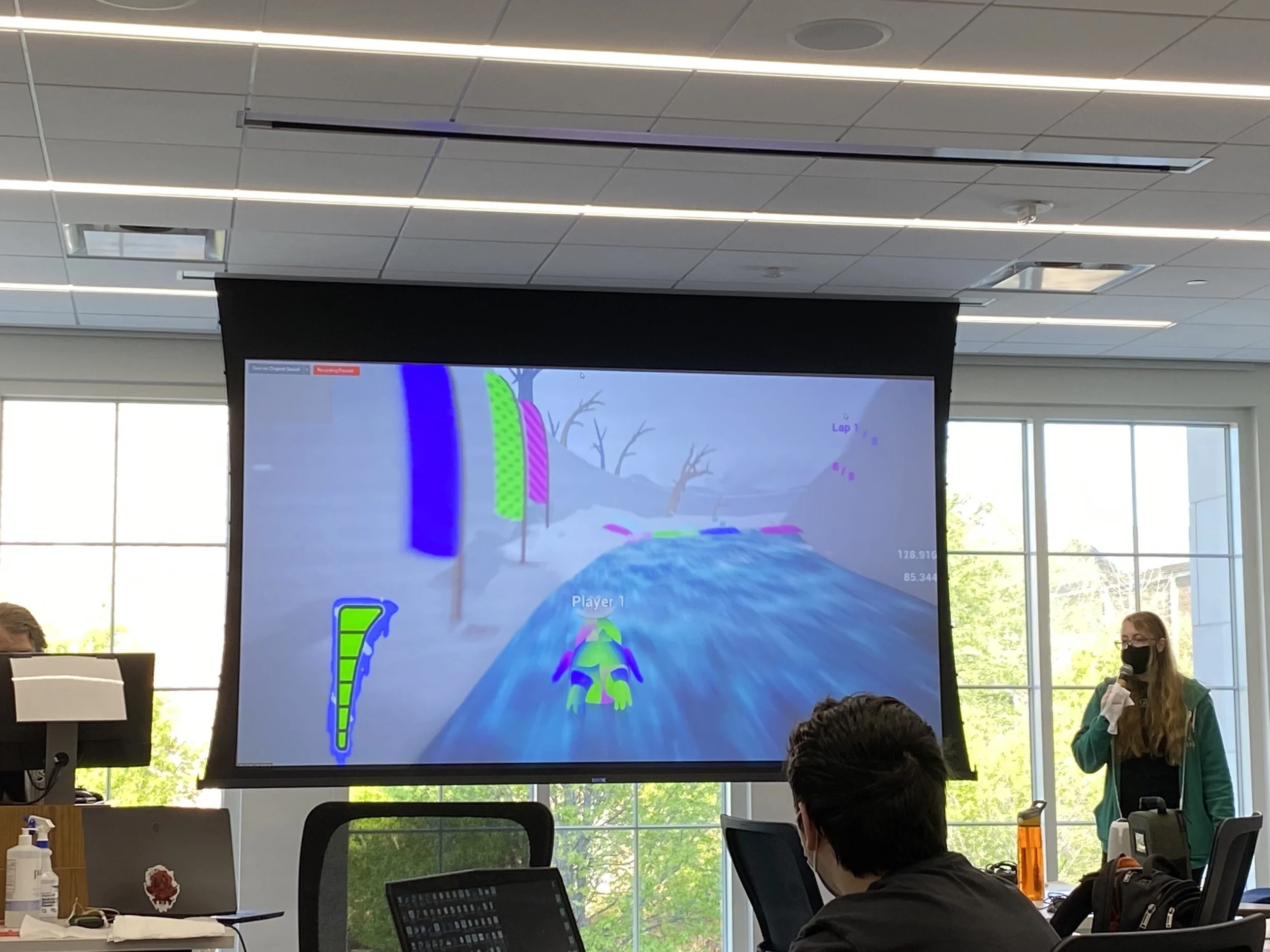

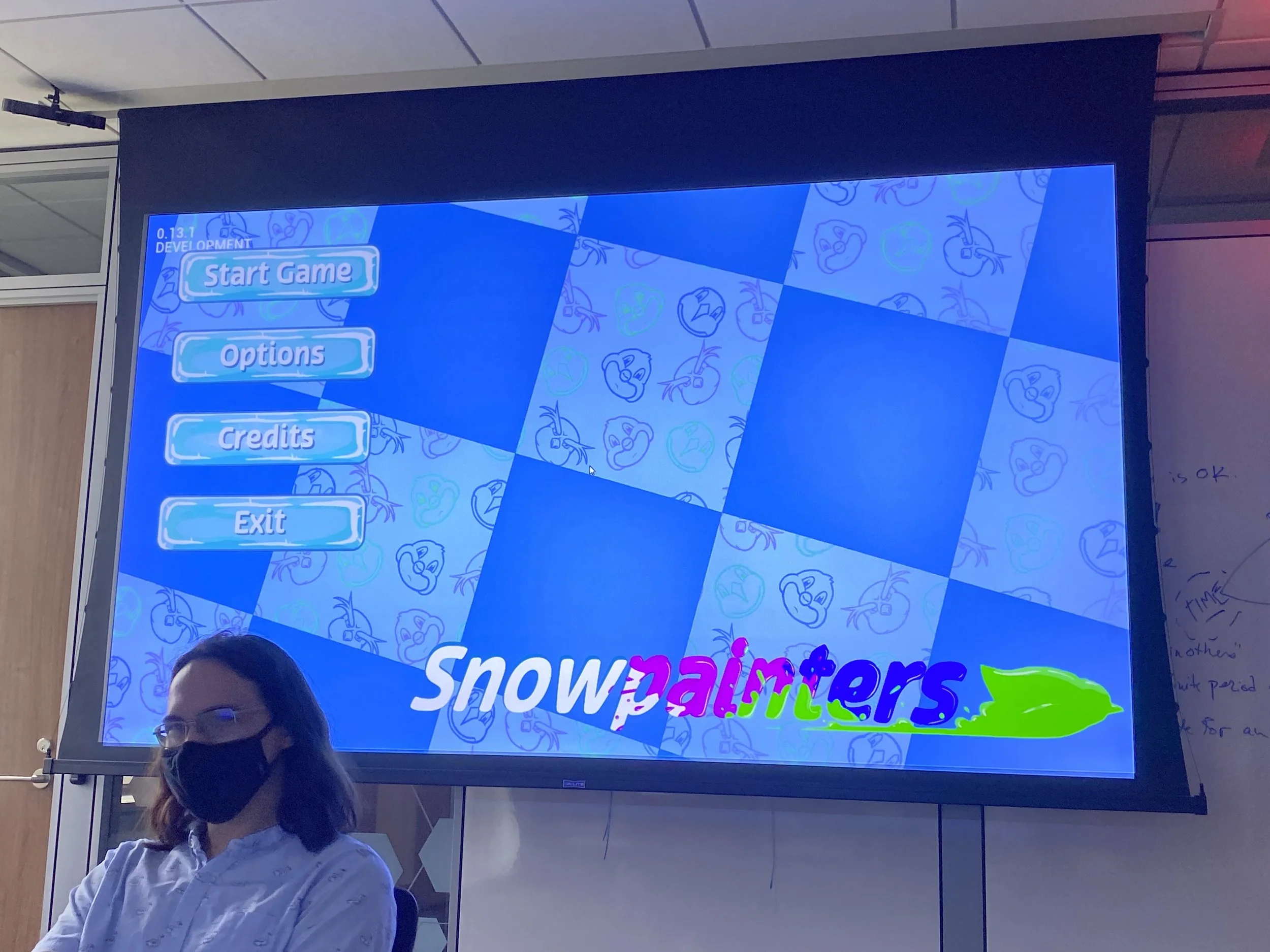

Snowpainters

Art Producer

February 2021 - May 2021

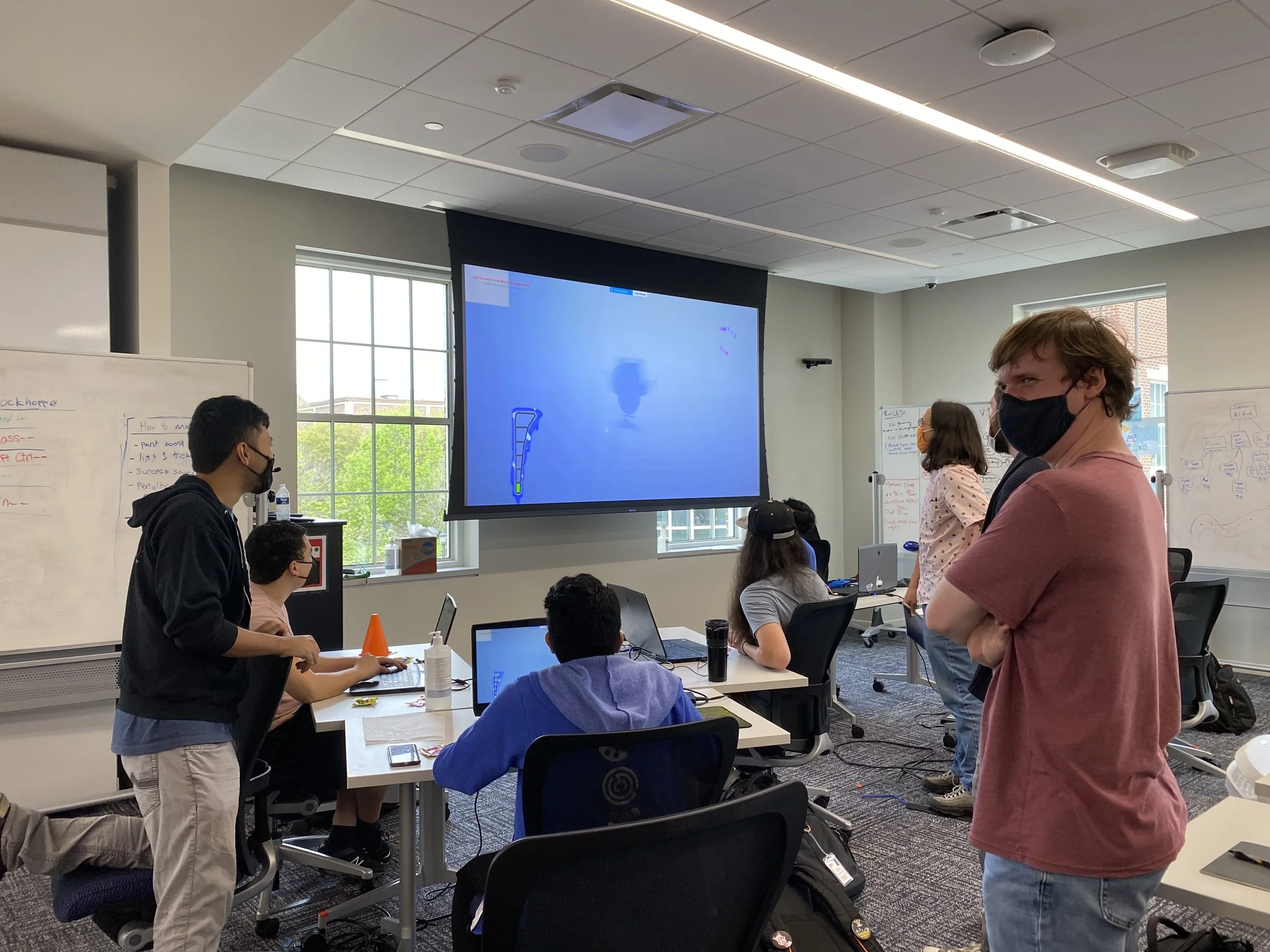

Snowpainters was created by forty developers over a span of 3 months at SMU Guildhall as part of their Team Game Project curriculum.

At SMU Guildhall, the curriculum includes three Team Game Project courses, where students learn about interdisciplinary collaboration by creating a game from concept to release. The first is a mobile game, which you can read about here. The second project, detailed in this postmortem, is a 3D racing game for the computer built in Unreal by the entire cohort working together. Here, producers finally get to put their project management learnings into practice.

My contributions:

Organized & managed seven artists alongside Art Lead to scope each milestone’s work & build dependency-driven asset schedules with the constraint of a small art team in mind

Developed, implemented, managed, and iterated production pipelines between artists, programmers, and level designers, leading to smooth collaboration across departments

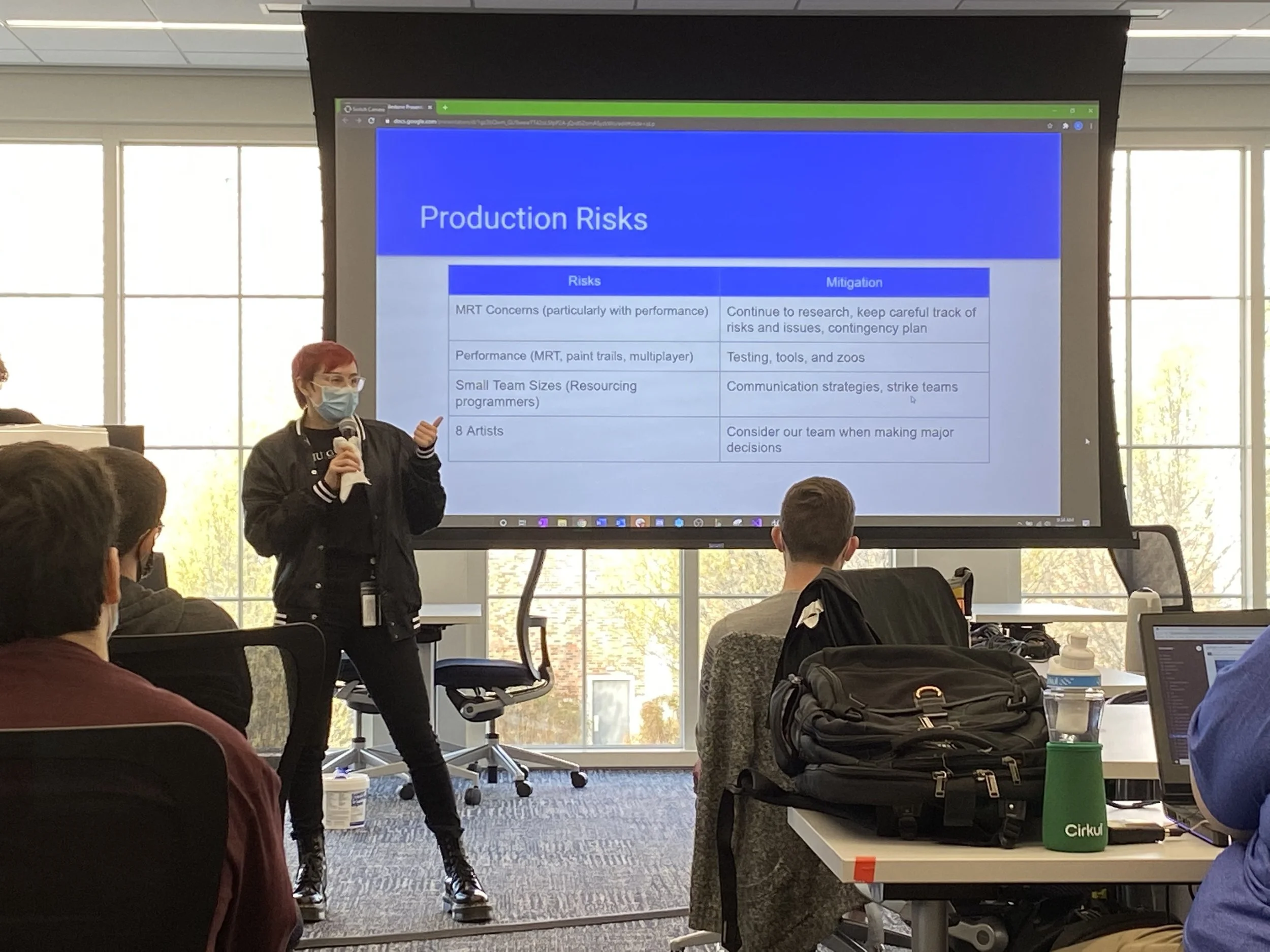

Proactively identified risks & contingencies for project features, making necessary pivots later on easier to implement

The Idea

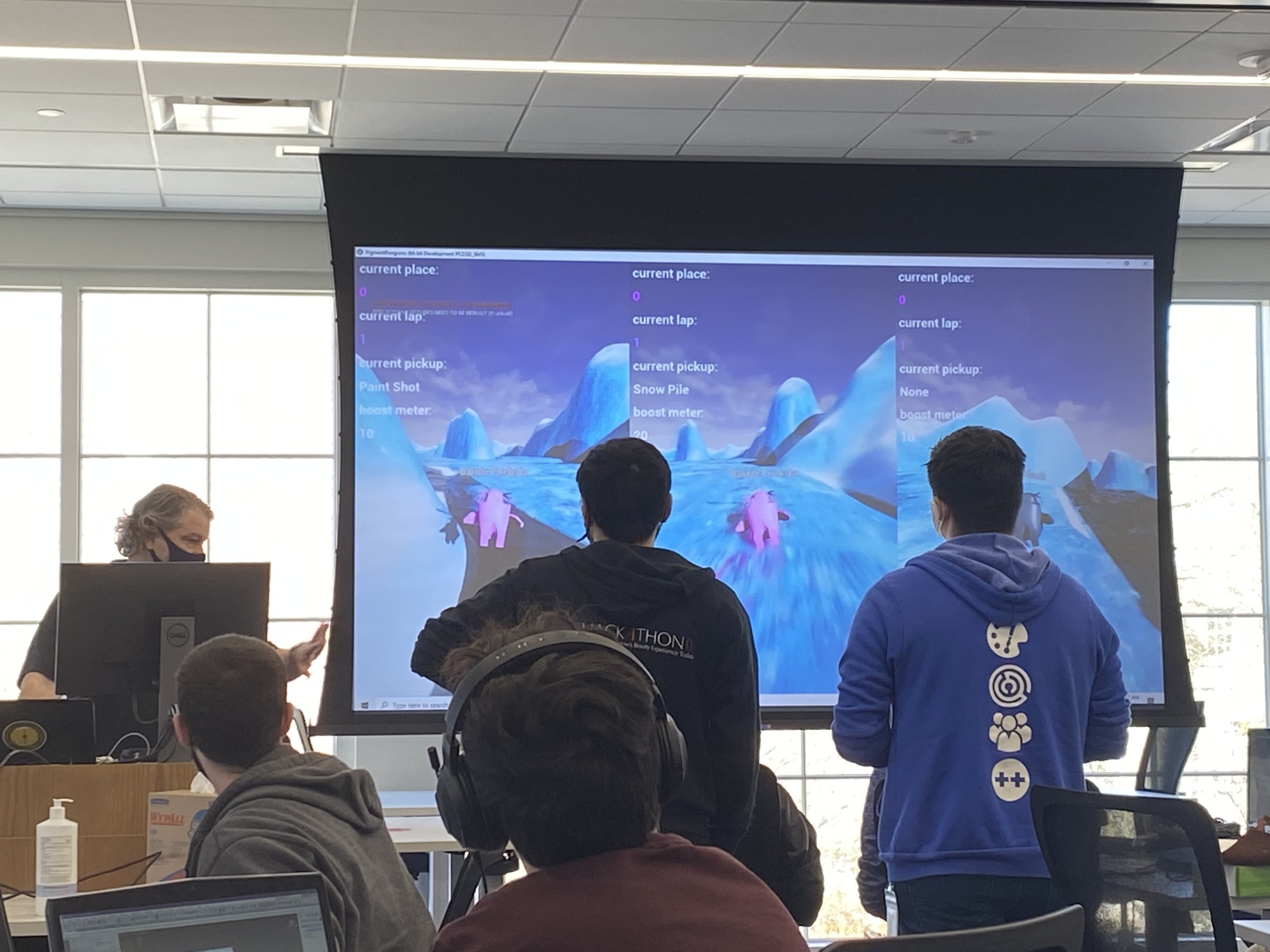

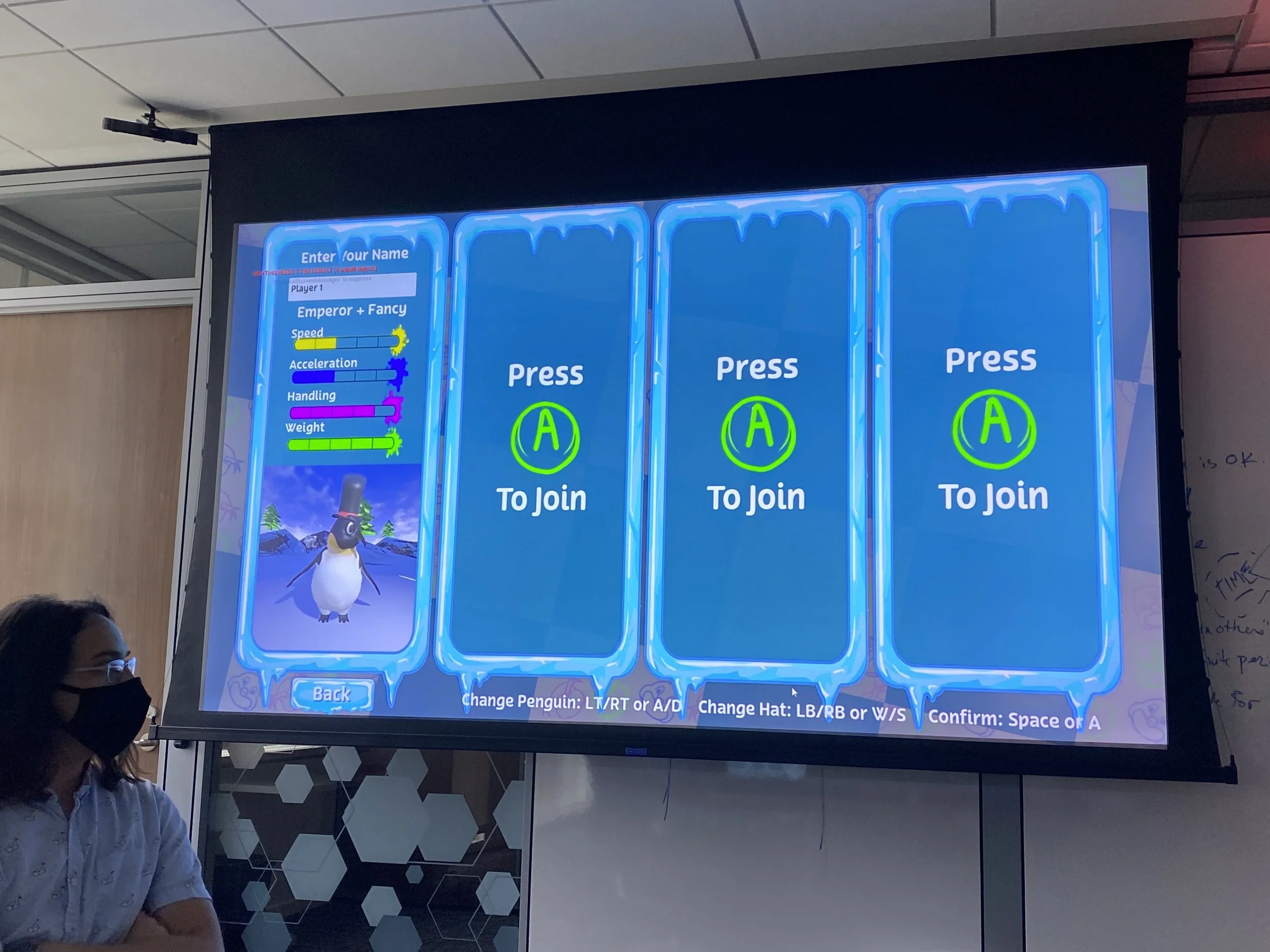

Our Game Designer Dakota Loupe began by brainstorming with the rest of our leads team to come up with the concept for our kart racing game. The idea was you play as a cute penguin in an icy environment, painting over it in different colors and using that paint to boost yourself as you race. The paint sliding mechanic works to dynamically balance the game, helping players behind catch up, and it adds a strategic element for the players in front, since their actions might benefit the racers behind them. We kept the phrase “easy to learn, difficult to master” in mind as we developed, keeping the game simple enough for young children to play while still satisfying for more experienced gamers.

The Process

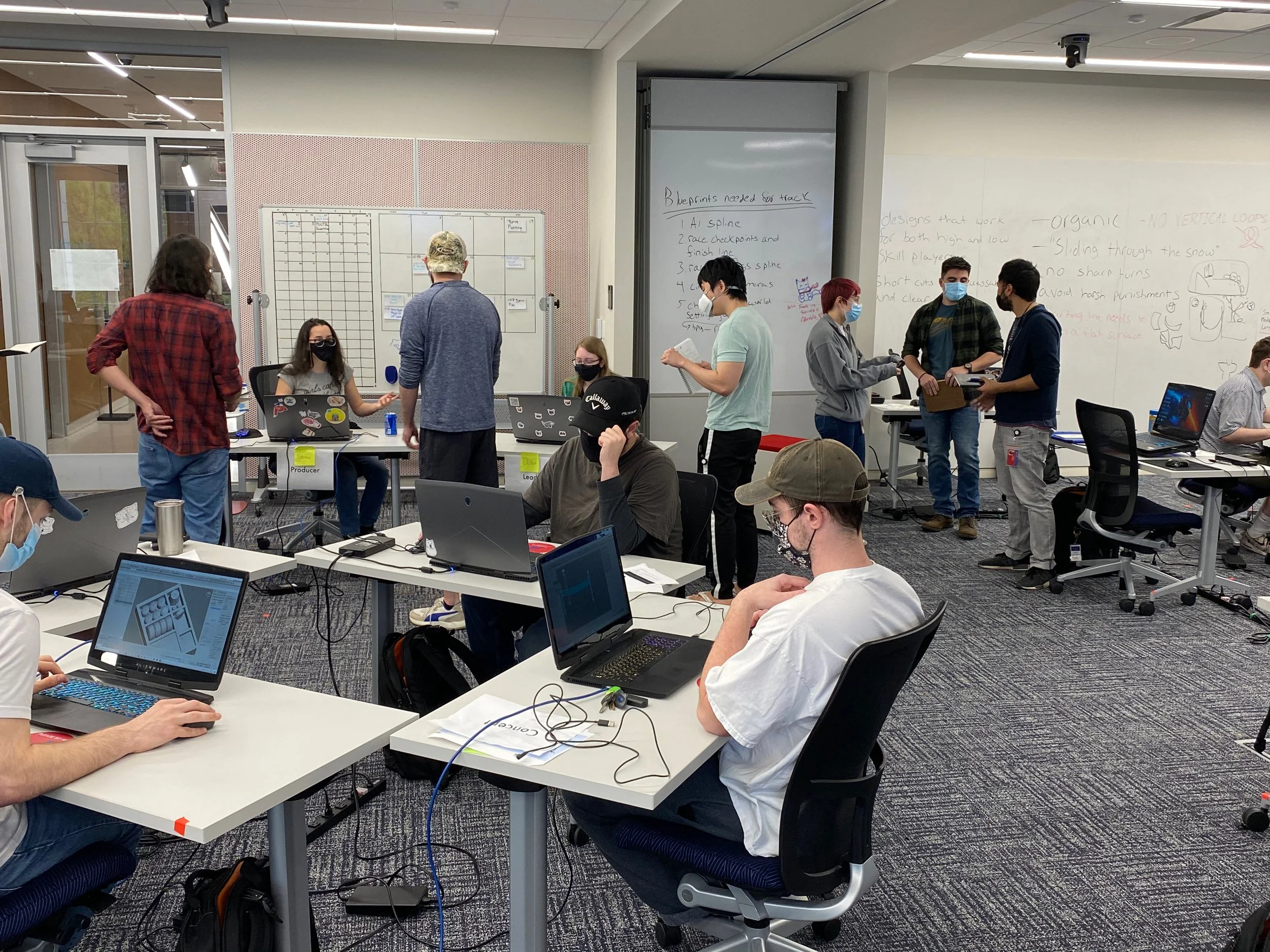

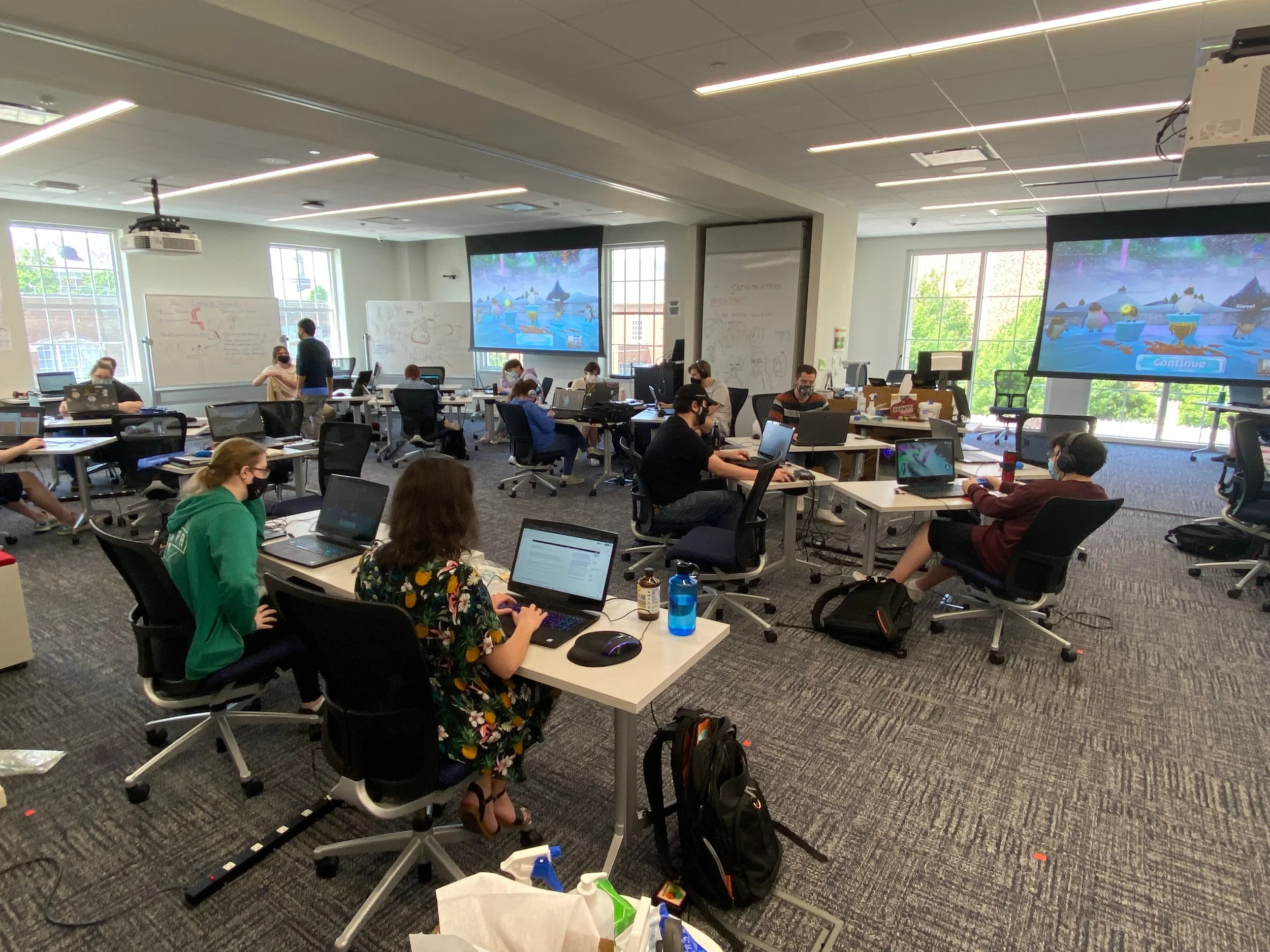

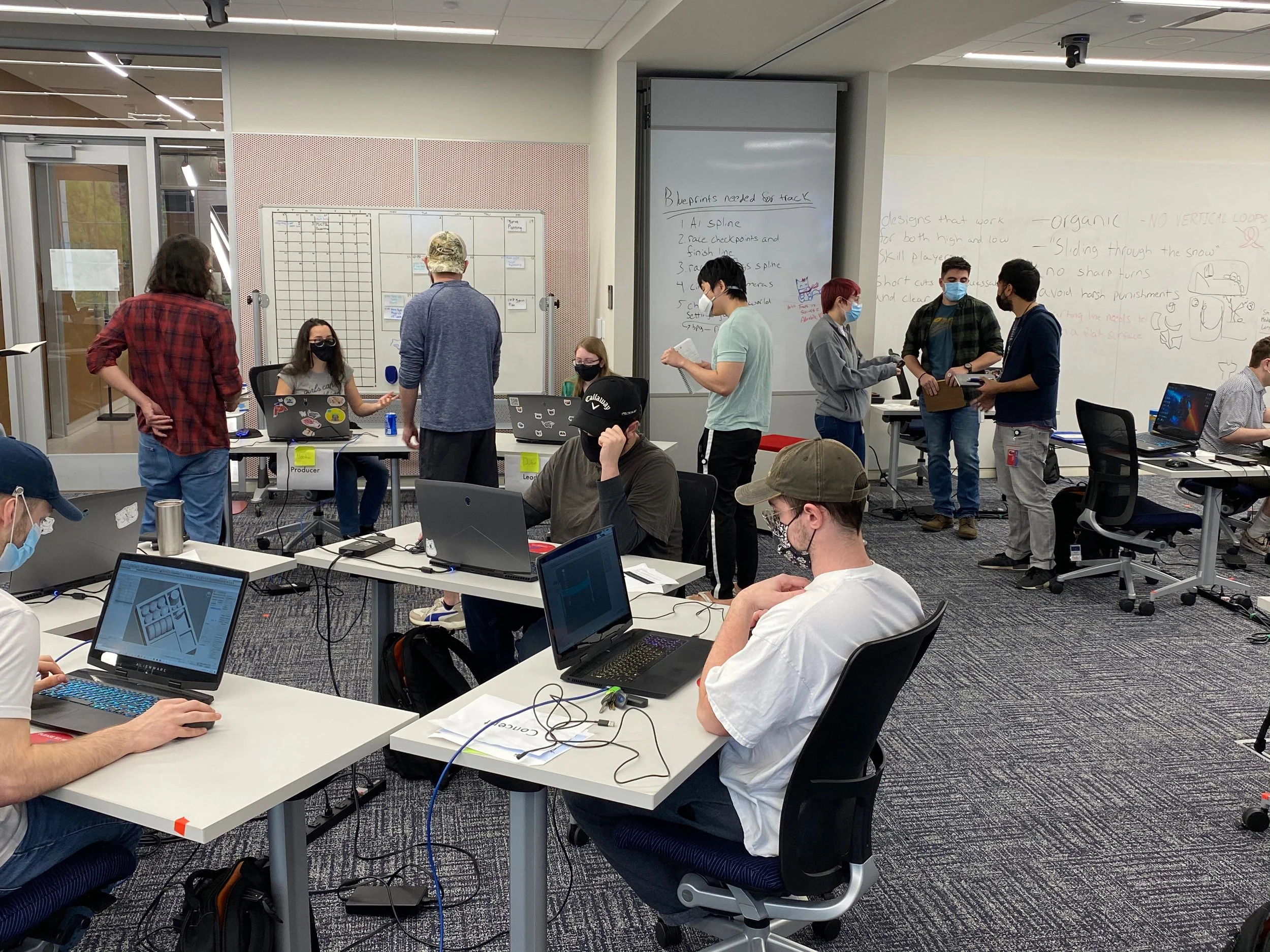

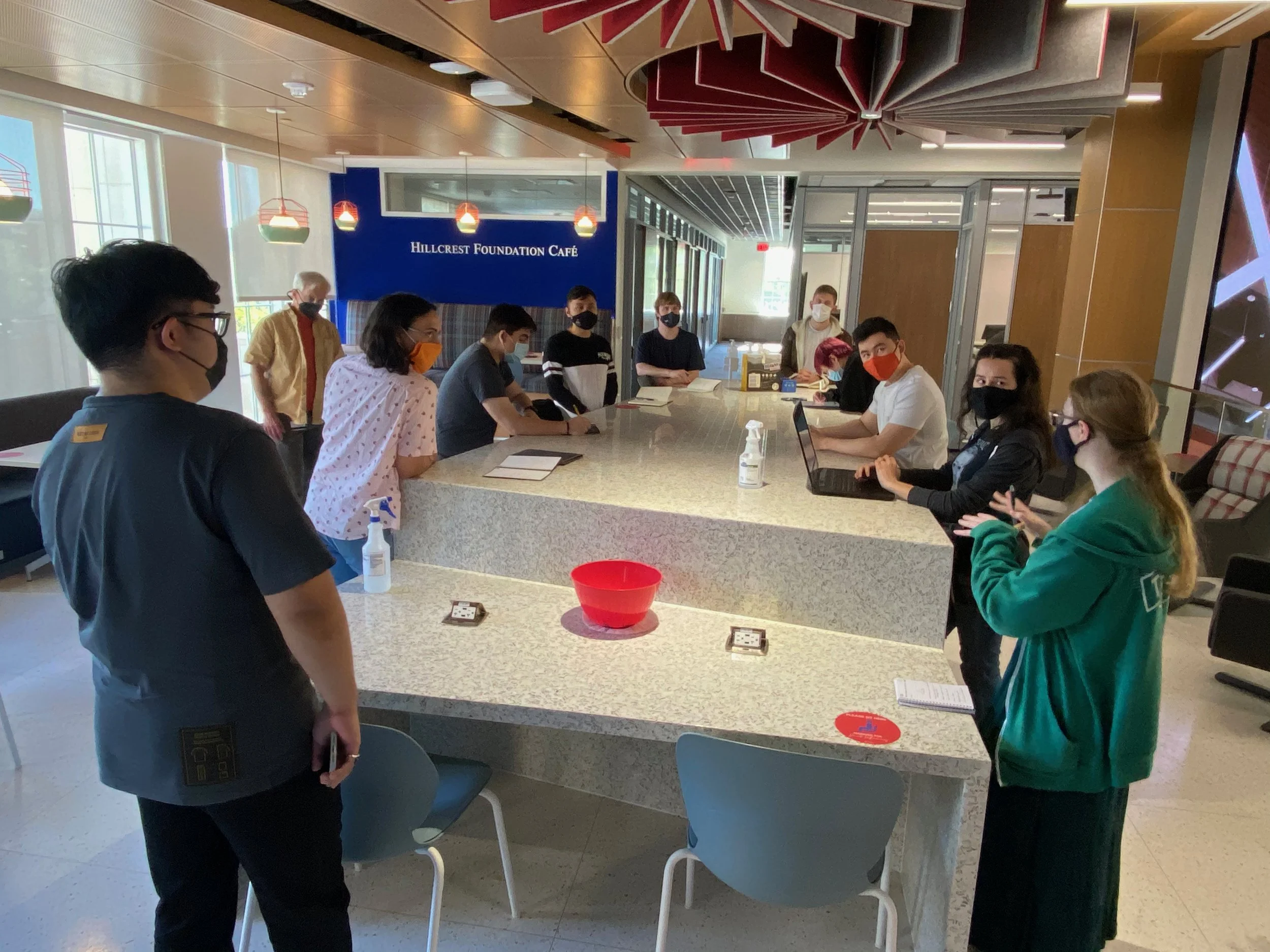

Every morning, all ten leads would scrum with their respective teams before meeting to discuss the day’s priorities and any cross-departmental work to be done. Our work days were three hours long and our milestones only lasted two weeks, so efficiency and clear communication were key.

Because Snowpainters was developed during the pandemic, work was primarily done in person with accommodations set up for working remotely. We had a main Zoom room for the 40-person team to work in, as well as breakout rooms for smaller teams to collaborate in. To assist hybrid teams, we used Owl cameras so that remote teammates could clearly hear and see everyone while working from home.

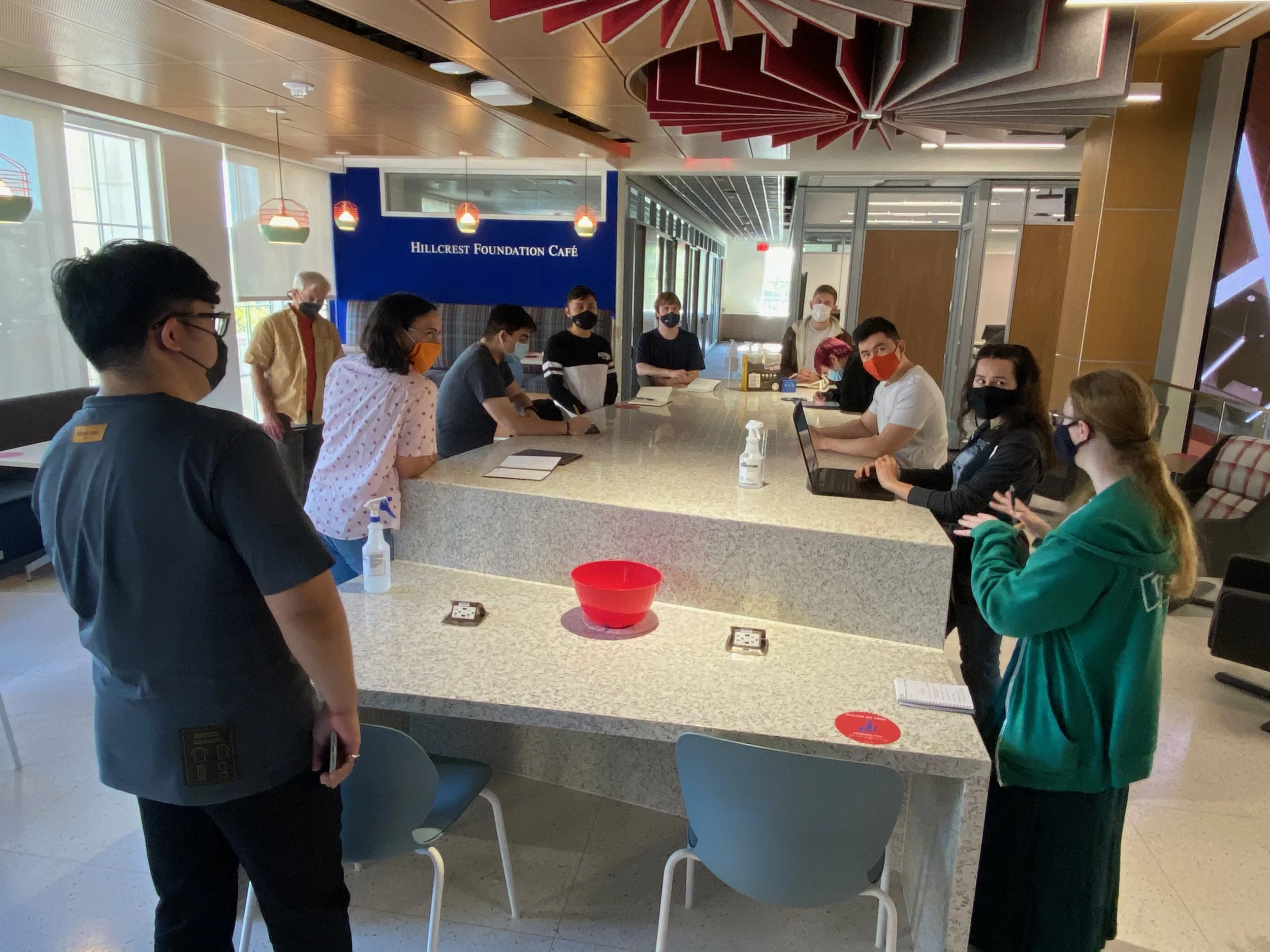

The Leads Team

What Went Well

Embrace the Constraint

Throughout the development, our slogan was “embrace the constraint,” a reminder that our 40-person team only had so much time and ability to create the game we dreamt of—and that one of our main bottlenecks was a seven-person art team that we could not afford to overload.

While all the leads did this, our Art Lead Lauren Dube and I especially did a good job of scoping and tracking work to avoid overloading our team. She developed a cute, simplistic art style and the two of us reduced scope wherever we saw the risk of our artists being overworked, making use of what we already had to create a rich world for our game.

Strong Communication

Throughout development, we maintained strong communication on every level. Our leads communicated effectively with each other, our teams, and our stakeholders—not just during meetings and presentations, but every day of the project cycle. This strength ensured that we were able to successfully execute our vision, help the team handle the disappointment of pivots or cut work, and address conflicts between different groups.

In addition to our morning scrums, the producers would post daily updates at the end of each day, covering what each team had accomplished. This would inform our morning meetings before the work day started, and helped us set effective priorities for our team scrums.

Conflict Resolution

Building off of the previous point, as soon as the leads were made aware of a conflict, we worked to resolve it as soon as possible. After discussing the root of the problem and desired outcomes in a meeting, the appropriate lead would sit and talk with the team members involved until they came to a satisfactory solution, making sure our team stayed unified.

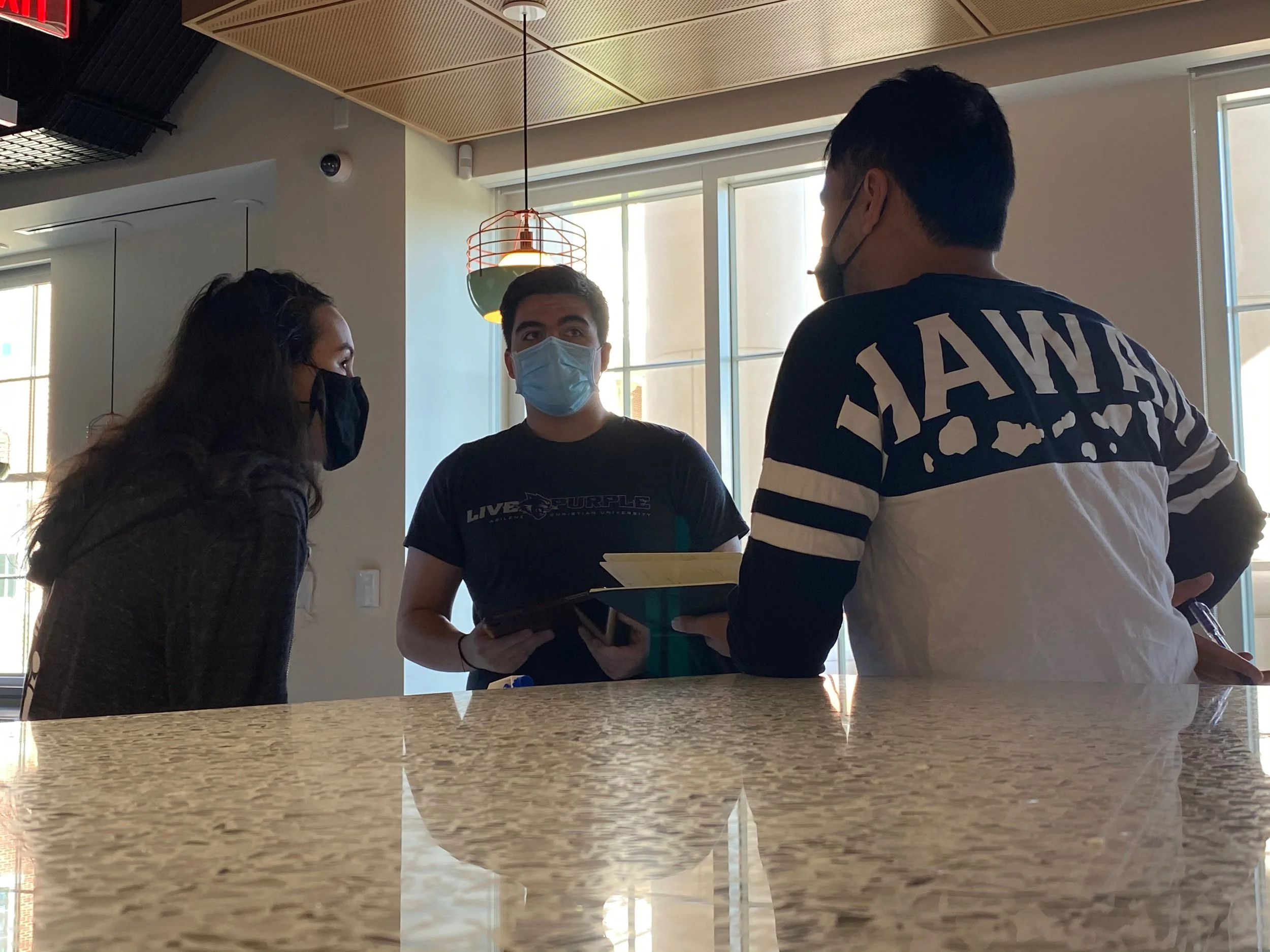

For example, when we discovered conflict between the Level Design and Art teams, Dube and I spoke with individuals on the art team to hear their perspectives; at the same time, we asked the Level Design Lead Will Santos and the Level Design Producer Daniel Reynolds to do the same with the level design team. I took the issues shared to create a loose agenda structured to achieve our desired outcome—a better relationship between the two teams. Then, the other three leads and I asked everyone on both teams to sit down in a room and discuss them. It led to stronger collaboration and an improved relationship between both teams moving forward, but it had some downsides, which I’ll discuss below.

What Went Wrong

Tension between Art and Design

By the time we reached our later milestones, the level designers and artists had developed a slight antagonism towards each other, making collaboration tense. When we investigated the reasons for this, we found that both sides felt unappreciated by the other and didn’t fully understand each other’s responsibilities in the pipeline. In order to resolve this conflict, everyone on both teams took a half a day off from work to share their feelings. Once these feelings were addressed, we asked the two teams clarify some confusing terminology and explain their respective roles in the pipeline. For example, while both teams worked together to complete “beauty passes” on the levels, the level designers had a different understanding of the term than the artists did due to how it was used in their own level design curriculum.

This clarification greatly improved our collaboration and boosted morale, allowing us to create more effective Level Design/Art strike teams, but it also lost us half a day of work in Beta. Because the individual teammates had let their issues grow so much before sharing them with their leads, we were unable to address them before they became a major concern. While having an intervention like this ended up being effective, it could have been prevented entirely, which I will elaborate on under Learnings.

Lack of UI Ownership

Due to a lack of ownership of our UI features and poor communication between the art and programming halves of the team, Dube and I had an incomplete picture of the UI work needed for the end of development. Because of this, we had to scramble to make up the work in Beta, placing avoidable pressure on our artists.

To address the miscommunications uncovered during our Alpha milestone, we had everyone who’d worked on UX/UI do an additional retrospective to improve our workflow before starting Beta. We also made sure that all relevant leadership was added to UI communications so they weren’t left out during the decision-making process. Finally, during Beta, we had more UI-centric meetings and strike teams, helping us polish a beautiful menu system for our game.

Learnings

Prevent Tensions from Forming

To prevent antagonism from developing, leads and producers can make sure their teams have a strong understanding of the other disciplines’ responsibilities. Common terminology can be clearly defined early on and repeated often to ensure that different disciplines are referring to the same thing. Leads and producers can also take the time to explain to their team what each stage of a pipeline includes so that individual contributors understand the context of their work and the value they provide to their teammates.

By helping people understand how their collaborators’ work relates to theirs, a leader can help their team appreciate their colleagues’ efforts and their own part in the pipeline. Additionally, when discussing issues in a cross-discipline pipeline, a leader can focus the conversation on what about the process is failing, directing their team away from placing blame on individuals. By keeping the conversation constructive and solution-oriented, a leader can turn venting into something that will be useful to improving interdisciplinary relations.

Dedicate More Attention to Ownerless Features

Ideally, every feature in your game will have a single owner who is responsible for its success, but this is not always the case. When a multidisciplinary feature doesn’t have an owner, it’s up to everyone to make sure that roles and responsibilities are clearly defined so that collaboration can go as smoothly as possible. As a lead, make sure to communicate early and often to everyone what your team is working on, how it will solve the other teams’ needs, and what you’ll need from them in order to complete your part of the work. By having unity, clarity of vision, and frequent check-ins, leads can make this complicated juggle easier on themselves.

Emphasize Communication for Better Collaboration

For the most part, there were very few issues when developing Snowpainters, and the majority of our success can be attributed to our frequent communication. In addition to our daily scrums, we had leads meetings every other day before work began to establish priorities, and many impromptu meetings throughout the day focused on specific features. We regularly discussed risks and concerns with our stakeholders, making it easier to find solutions or pivot before we’d invested too many resources in something unachievable. And, most importantly, we nurtured the team’s passion for the project by keeping them involved and informed about our decisions as leads so that we could keep as much of their work in the game as possible.

While Snowpainters was our cohort’s second Team Game Project, it was the first game we shipped to Steam—something that isn’t an expectation of the course, and which we were the second cohort in Guildhall history to have achieved. The fact that we created something so polished as to be published so early in our careers was a monumental accomplishment that we’re all deeply proud of. I encourage you to explore our winter wonderland yourself, maybe even with some friends, by downloading it for free on Steam today.

%20%E2%80%94%20Nooka%20Dascalu_files/Headshot_Cartoon_transparent.png)